America’s Lost National Parks Posters

Between 1938 and 1941, America’s national parks were celebrated in a series of silkscreened posters that, thanks to a park ranger, are coming back to life

Between 1938 and 1941, America’s national parks were celebrated in a series of silkscreened posters that, thanks to a park ranger, are coming back to life

Park ranger Doug Leen used to save teeth, now it’s posters. The former Seattle dentist has dedicated himself to rescuing a remarkable series of late-1930s serigraphs celebrating America’s national parks. These silkscreen posters were originally commissioned by President Franklin D Roosevelt’s Works Projects Administration (WPA) as part of his post-Depression New Deal, to honour the National Parks Service (NPS), which is currently celebrating its centennial.

The WPA’s role was to find jobs for eight million unemployed Americans. Many were recruited to construction projects, while others were responsible for creating some 475,000 works of art, from pieces of music to public murals in Federal Art Projects.

Park art

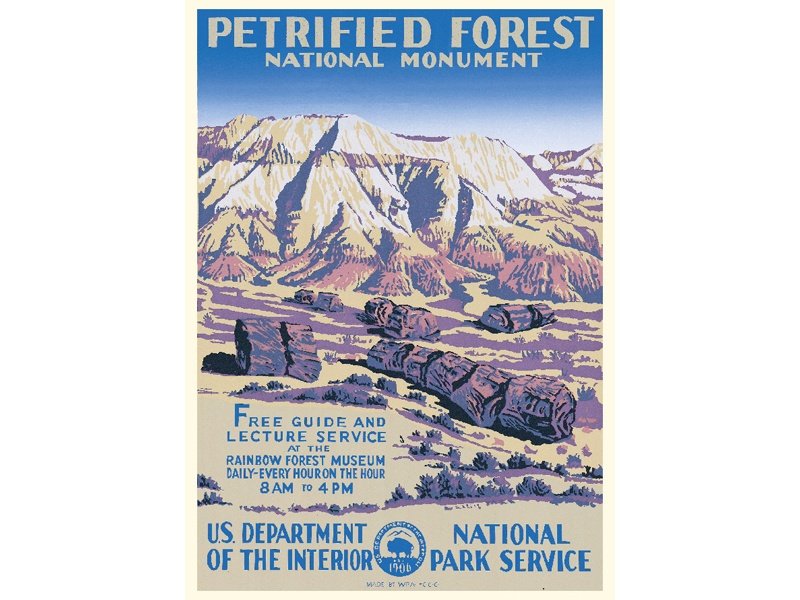

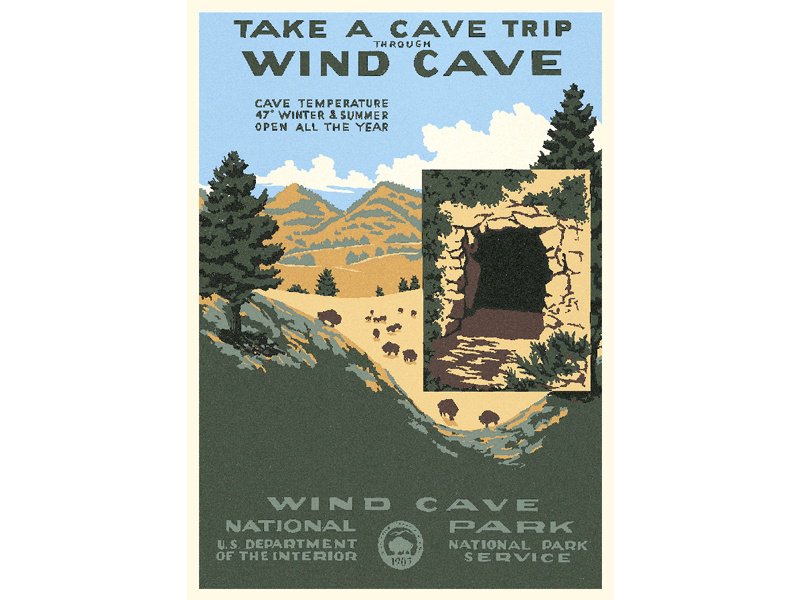

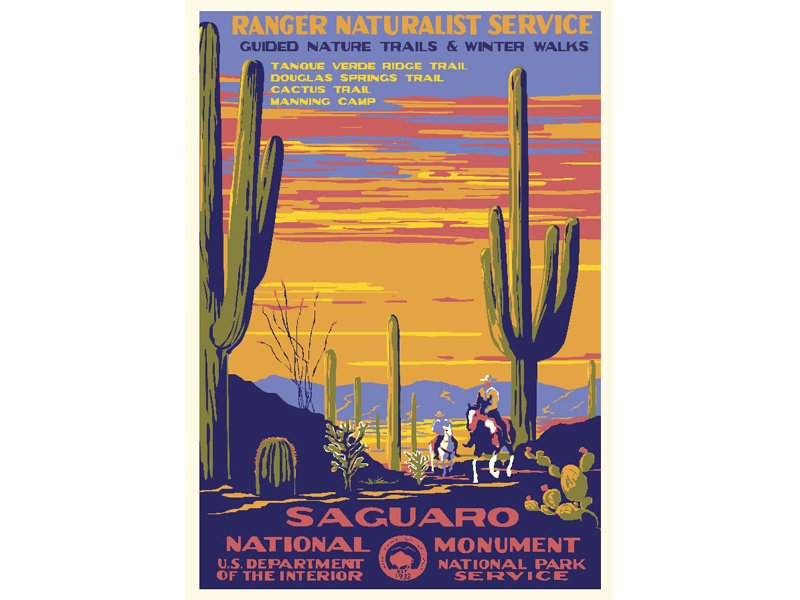

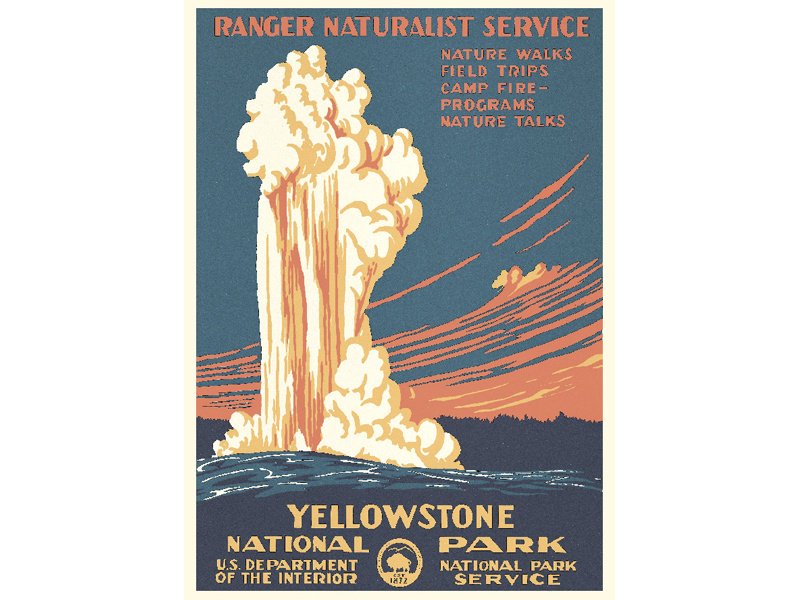

Among these initiatives was a serigraphic poster series celebrating the country’s 58 National Parks, from Acadia to Zion. However, only 14 parks were represented between 1938 and 1941, with each image printed just 100 times, before World War II halted the project.

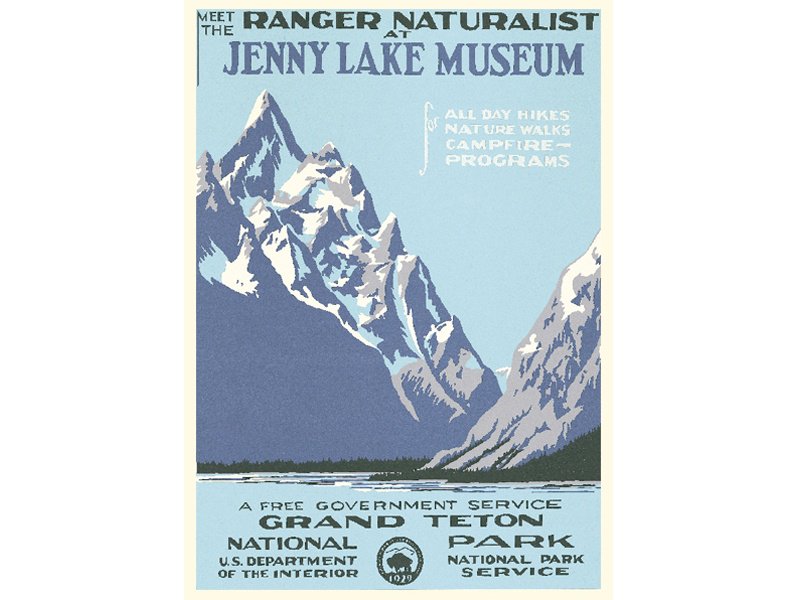

“They were ephemera,” says Leen, aka Ranger Doug, a seasonal park ranger who spent seven years caring for Grand Teton, Wyoming. It was there, in 1971, that he spotted one of these posters destined for the scrapheap.

“They were created to encourage people to visit the parks, but when war began, they were torn down, colour-crayoned over by kids, and eventually ended up in the trash,” says Leen. “What remained at the Western Museum Laboratories in Berkeley, California – where WPA artists printed the posters – was sent to the Federal Archives in San Francisco, and in 1950 they were returned to their respective parks. It could be one of those I found at Grand Teton.”

The lone ranger turned poster boy

The beauty of the Grand Teton poster struck Leen: “At first I didn’t know what exactly I’d found, but I knew it didn’t belong in the dump. It was well made, mounted on hardboard, and silkscreened. I suspected other copies might exist, that other parks might have similar posters. But initially I hung it on the wall of my log cabin up at Jenny Lake and just enjoyed it.”

His curiosity piqued, Leen spent the next two decades hunting for similar posters and the story behind them. He learned they were probably designed by WPA artist Chester Don Powell and printed by screen printer Dale Miller. It was after finding 13 monochrome negatives in the National Park Service archives in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, that Leen decided to reprint the lost series himself. As word got out, originals began resurfacing.

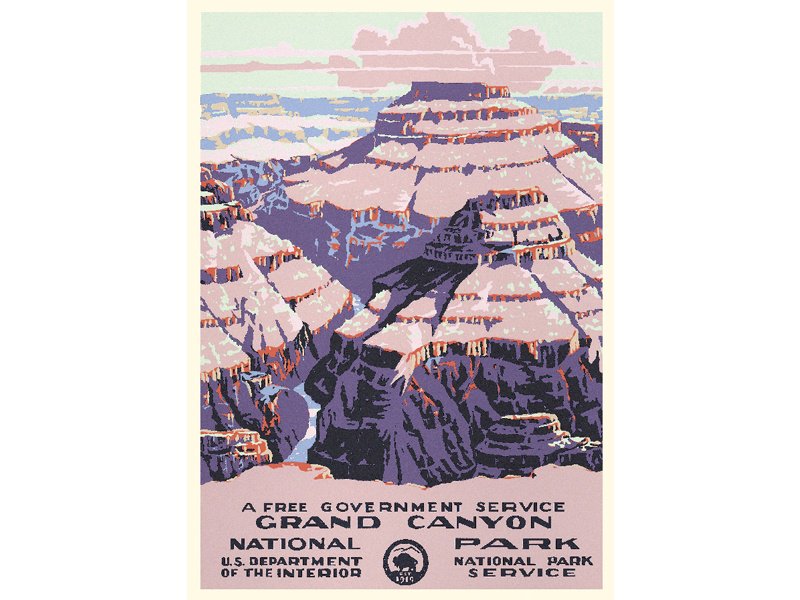

Two Mount Rainier posters appeared in a garage near Seattle, found under a park log cabin years earlier. Three more turned up sandwiched inside an original frame, the middle one in pristine condition. A Grand Canyon and Petrified Forest were found in National Parks archives, and in 2003 researchers at Bandelier National Monument discovered 13 posters in a file drawer – some of which had been chopped up and used as cardboard dividers; one was being used to fill a plant-press. An LA art collector found nine originals in a second-hand shop in 2002 that later sold at auction in New York City. A California attic yielded six more. Today, 42 originals out of 1,400 have been found, with only one copy each for Yosemite, Yellowstone Falls, and Petrified Forest.

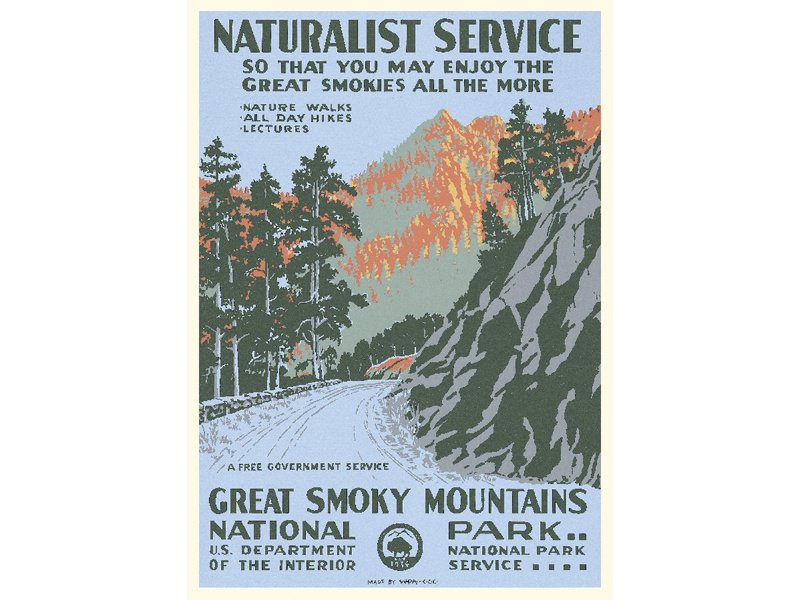

Putting a value on the Grand Canyon

“Of the 14 original designs, I’ve located 12, and 11 are now back in the public domain in the Library of Congress,” says Leen. “The two still missing are Great Smoky Mountain and Wind Cave, though we have reasonable black and white photographs of them. I’ve offered $5,000 rewards for to be donated back to the public domain. Most of the discoveries have been in California, where they were printed. My goal is to find them all and put together an exhibition.”

It cost $12 to produce 100 prints in the 1930s. Leen had one of his early prints valued for $1,800 in 1999. In 2005 a Grand Canyon sold at auction for $9,000. “I wouldn’t be surprised to see a print sell for between $10,000 and $20,000 today,” he says. “Iconic parks like Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and Yosemite would probably fetch the best price at auction. Condition and number of known copies would be a factor, too.”

Ranger of the lost art

Does he have a favourite? “Grand Teton, for two reasons: it was the first one made by the WPS, and comes with the original letter describing why it was made. Secondly, I worked there as a ranger and found the print that started this whole odyssey. But they’re all different, and I love them all.”

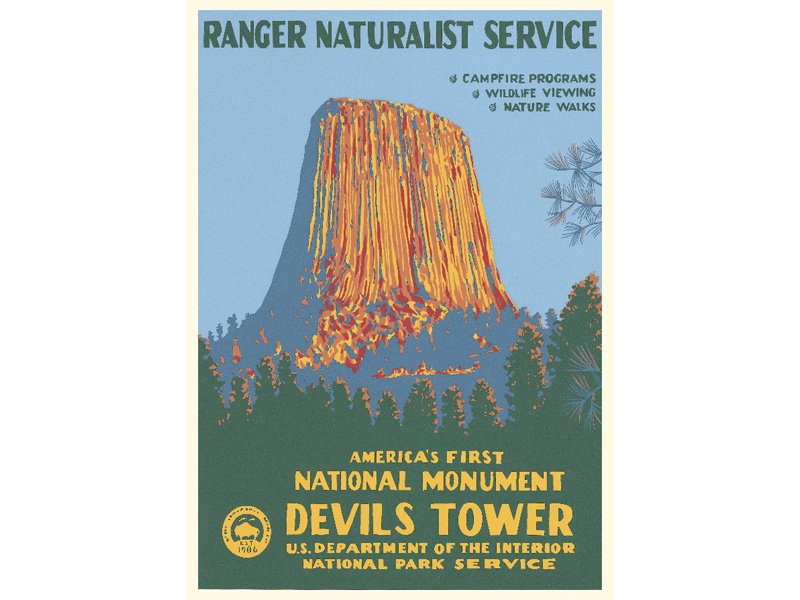

But Leen – dubbed “Ranger of the Lost Art” – hasn’t stopped at sourcing vintage posters, he now makes contemporary prints in the style of the WPA originals. So far he has created 25. “I started making new ones, largely due to demand from parks not featured in the original series,” he explains. “I realized this style could be exported to every park, and computers would allow them to be created fairly simply. There were hurdles, though: the Devils Tower poster was our first contemporary design, created before computers were sophisticated enough to help, so it was very time-consuming and expensive.”

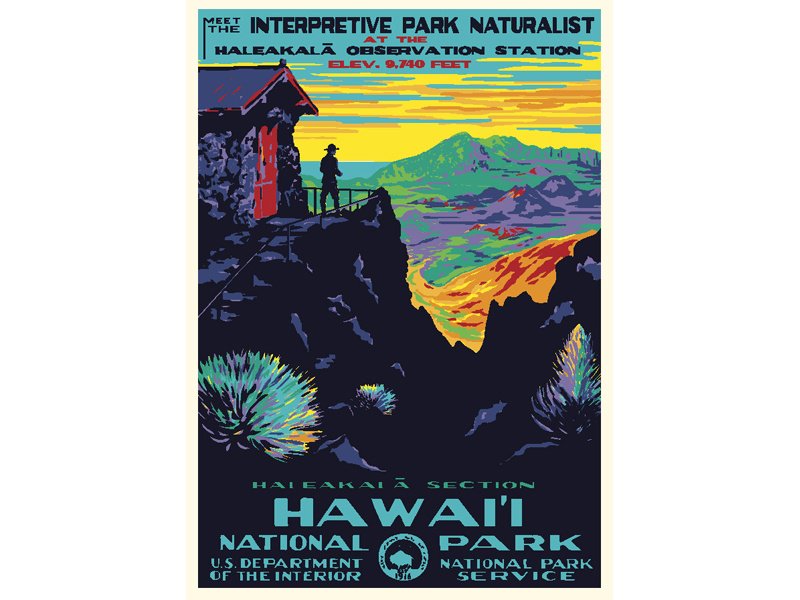

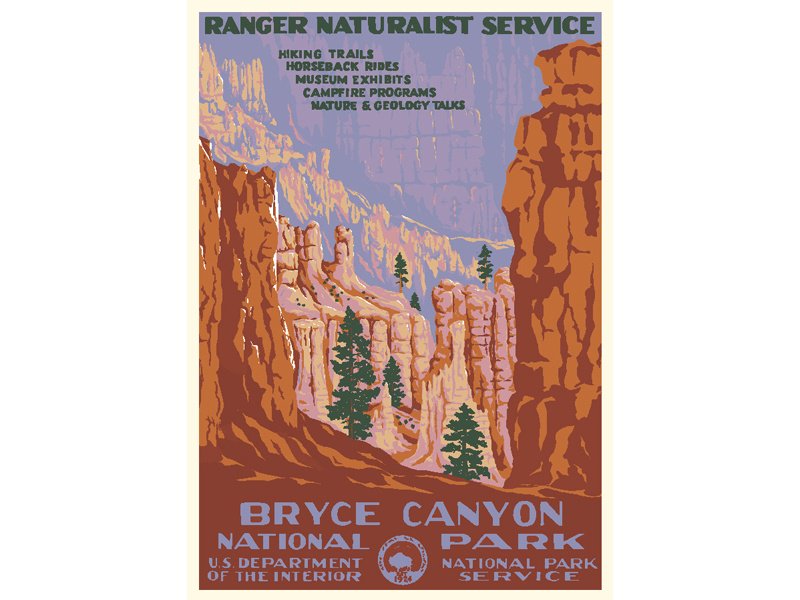

That was 20 years ago, and the Devils Tower painting now lives in the NPS archives. Bryce Canyon was the first computer-generated design Leen attempted with his co-artist Brian Maebius, and after initial teething problems the duo are now creating bolder and more colourful designs with more printed screens: General Grant, Saguaro, and Haleakala each have ten.

“Ultimately, I’d like to produce a serigraph for every NPS park and monument,” he announces. “There are 413 and we’ve made about 50. But a first edition costs $20,000 for 1000 copies, and since my profits on this are typically zero I need a large park or a large commitment before I can produce them.”

“Competitors do produce similar prints but many are poor quality. I consider my designs art, not posters. I’m convinced I can make a comprehensive set of NPS park serigraphs, and my hope is that this could be coordinated by the NPS, just as it was at the beginning in 1938 with the WPA.”